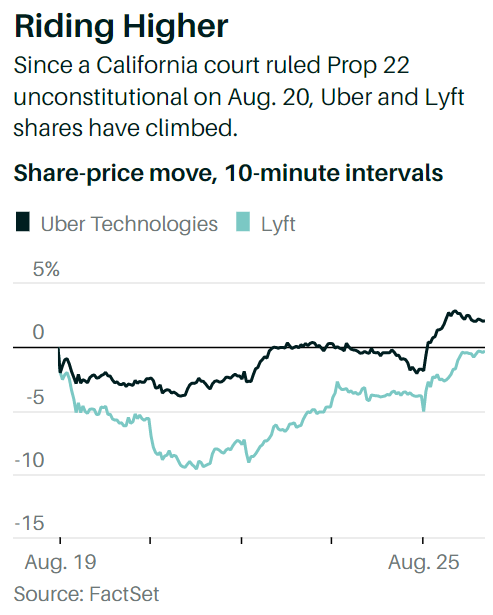

After a California court on Aug. 20 struck down a state law exempting Uber Technologies andLyftfrom having to classify their drivers as employees, Wall Street analysts largely shrugged. Some legal experts, however, say the companies could end up paying billions of dollars in back and future pay, benefits, and penalties—though a day of reckoning could take awhile.

Proposition 22, as the law is called, took effect on Dec. 16 on the heels of a $205 million campaign backed by app-based ride-share and delivery companies including Uber (ticker: UBER) and Lyft (LYFT). While it allows ride-share and delivery employers to classify workers as independent contractors, the law also provides for healthcare subsidies, a minimum earning guarantee, vehicle expenses at about half the federal rate, and insurance. This is still well short of the benefits California requires for employees.

California Superior Court Judge Frank Roesch declared Prop 22,which was challenged by the Service Employees International Union together with a group of gig drivers, to be unconstitutional. In his ruling Friday, Roesch anticipated the argument that previous courts have often honored the will of voters when they passed ballot initiatives. He wrote that California’s Constitution devotes strong language in reserving for the legislature power over the state workers’ compensation system — which drivers have been excluded from under Prop 22.

Roesch hasn’t ruled whether to grant a stay on his ruling pending appeal, though a move of that kind is common in such situations.

“On the merits they seem to be defeated fairly consistently. On the ability to drag it out, they have thus far kept the wolf away from the door,” said William B. Gould IV, a Stanford Law professor emeritus, who was among a group of law professors producing court briefs supporting the idea Prop 22 is unconstitutional.

The Protect App-Based Drivers & Services Coalition, an Uber-linked organization founded to back Prop 22, said:“We believe the judge made a serious error by ignoring a century’s worth of case law requiring the courts to guard the voters’ right of initiative.” The coalition also said it anticipates any order requiring the company to pay drivers as employees would be on hold until appeals were exhausted.

The companies’ sentiment was echoed by analysts, including Morningstar’s Ali Mogharabi, who wrote Monday that “strong support for the ballot measure in the November 2020 election, along with the California Supreme Court’s refusal to hear the case earlier this year, could sway the outcome in favor of Proposition 22.” The California Supreme Court in February dismissed the case without commenting on the merits, resulting in Friday’s lower-court ruling.

Mizuho’s James Lee reiterated his Buy rating on Uber shares despite the ruling. He and other analysts agree that Friday’s ruling is likely to be overturned because courts generally honor California voters’ constitutional authority to pass laws.

Legal experts aren’t so sure.“The judge’s ruling states that changing that would require a constitutional amendment,” said Ken Jacobs, chairman of the University of California, Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education. “Proposition 22 was not a constitutional amendment.”

If it makes its way back to the state Supreme Court on appeal, that body has a history of throwing out ballot initiatives deemed unconstitutional, such as ones described as denying civil rights to Blacks, and same sex couples, said Gould, who served as chairman of the National Labor Relations Board under President Bill Clinton. “Just because it’s part of a ballot process, and the people voted for it, is really irrelevant to its constitutionality,” he said. “The public can act unconstitutionally.”

The law also faces a number of other legal challenges now making their way through courts. On Jan.14, the state Supreme Court affirmed that California’s employee classification rules could be applied retroactively prior to the enactment of Prop. 22, and the city attorneys of San Francisco, Los Angeles and San Diego have vowed to pursue such retroactive claims. That bill could come to tens of billions of dollars, according to a Barron’s analysis of datafrom a 2019 University of California, Berkeley study.

“Uber and Lyft are responsible for reimbursing drivers for years of unpaid wages, benefits, and business expenses from before Prop 22 took effect,” said John Coté, spokesman for the San Francisco City Attorney’s office, which is involved in separate litigation concerning Prop 22. “With this latest decision, these companies may very well owe their drivers even more.”

If the SEIU were to prevail in its state constitutional challenge and Prop 22 were ultimately invalidated, the ongoing bill for future wages and benefits could be even greater.

As Barron’s reported in May, the city attorney lawsuits as well as litigation from California’s attorney general and labor commissioner are asking for what could be tens of billions of dollars in back pay and benefits.

A 2019 California state report had them driving 4.3 billion miles in 2018 alone. Repaid at an average Internal Revenue Service reimbursement rate of 56 cents per mile for four years would be $9.6 billion. And those expenses are only one portion of what plaintiffs allege the companies allegedly owe.

Gould believes the company may manage to fend off either outcome, either in court or with another ballot proposition.

“I have no doubt they will be able to keep the wolf away from the door for some period of time because of their considerable resources,” said Gould, who was among a group of law professors producing court briefs supporting the idea Prop 22 is unconstitutional.

Comments