Ride-hailing company isn’t becoming an online travel agent—it just wants people to spend more time on its app

You might be able to book your next vacation on Uber, but you won’t be able to book your next vacation with Uber. You aren’t the only one confused.

Headlines flew this past Wednesday suggesting that Uber Technologies was becoming the next Expedia after the Financial Times first reported that Uber would soon add long-distance travel bookings, including “trains, coaches and flights” to its U.K. app this year.

Despite Uber Chief Executive Dara Khosrowshahi’s background previously running the online travel agent, Uber doesn’t want to be Expedia. It just wants you to spend more time on its app—and to maybe rack up a little more of your business as a result.

Investors should think of this U.K. pilot a bit like Uber’s New York City taxi partnership—users will be able to book a train, like a taxi, through the Uber app and, for the business referral, Uber will receive a service fee. Unlike when you book a trip through Expedia, Uber won’t handle your train reservation (the train company will.) It will merely be the platform upon which you book it.

“We’re not running the boat,” an Uber spokesperson said. The financial implications of that are key. Uber is already expanding its business geographically and vertically in a dizzying number of ways. As of February, it was active in over 10,000 cities across 72 countries. It can deliver food, groceries, convenience goods, alcohol, flowers, prescriptions and even baby clothes.

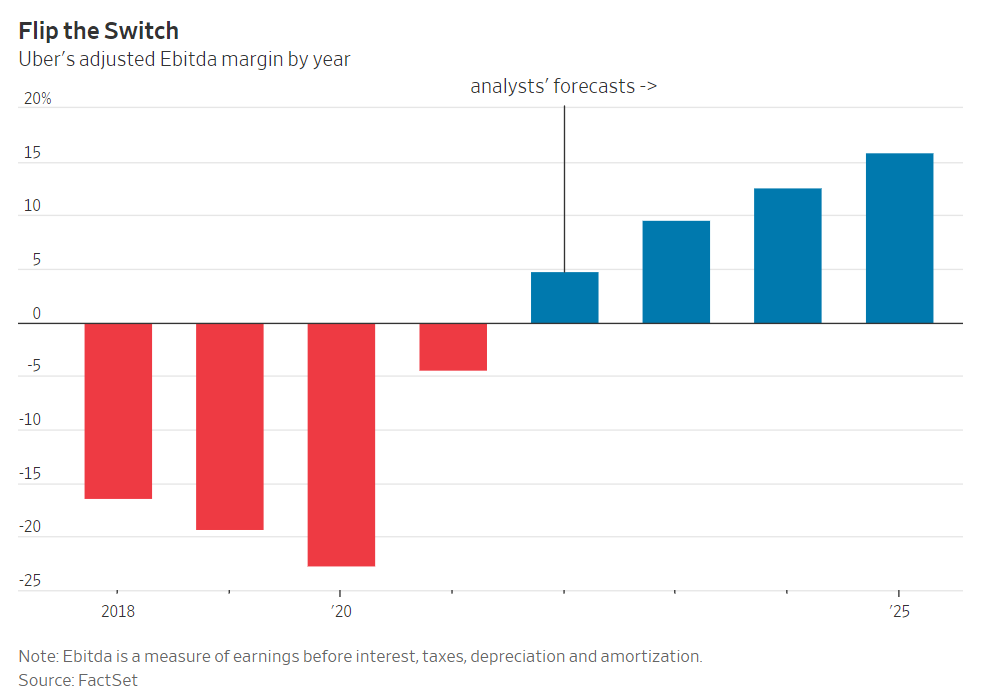

It can’t yet sustainably make money. Uber lost $774 million last year on the basis of adjusted earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization. In 2020, it lost over $2.5 billion on that basis, even while food delivery as a sector was thriving. So while online travel agents such as Expedia,Booking Holdings and even Airbnb boast healthy margins, Uber needs an asset-light model if it wants to continue to rapidly grow and have a hope of near-term profits.

Uber hasn’t specifically said why it is piloting its new services in the U.K., but as a major transit hub and one of Uber’s largest markets, it makes sense. Airport trips globally made up 15% of Uber’s mobility bookings pre-Covid 19 in 2018, according to Uber’s initial public offering filing, and the company has said 40% of its U.K. trips begin or end near a transit hub. AB Bernstein analyst Mark Shmulik estimates Uber could collect about 1% to 3% commissions on flight bookings, with hotel bookings garnering higher commission rates down the road.

The challenge will be changing consumer habits. If you are in London and want to book a train today from Heathrow, you consult Heathrow Express or Trainline. The hope is that you will grow to consult Uber. And once there, you might book an Uber to pick you up from the train station and take you to your final destination.

Uber says it will pilot trains and coaches on its U.K. app this summer, and plans to add flights and hotels later this year. The company hasn’t said whether the travel provider or the user (or both) will pay the service fee. Asking users to pay to change their habits could be a bit of a nonstarter, but then again Uber’s some $17.5 billion in revenue last year is a testament to how much consumers will pay for some incremental convenience.

Uber doesn’t want to manage all your travel; it just wants to be the first place you go.